Understanding Freytag’s Pyramid

Why Structure Matters in Storytelling

From fireside tales to big-screen blockbusters, stories have always needed some kind of shape. While styles and mediums evolve, the fundamental need for story structure remains. One enduring model—though often overshadowed by modern frameworks—is Freytag’s Pyramid, a 19th-century narrative map crafted by German writer Gustav Freytag.

Unlike the clean-cut arcs in today’s screenwriting guides, Freytag’s model offers a more nuanced rise and fall, rooted in classical drama. It’s still surprisingly relevant. Writers, screenwriters, playwrights—and even brand strategists—continue to lean on its structure to build emotionally resonant, gripping narratives.

Let’s unpack what this pyramid actually is, how it functions, and how you might (with a few adaptations) use it to elevate your own storytelling.

Breaking Down the Pyramid: The Five Stages

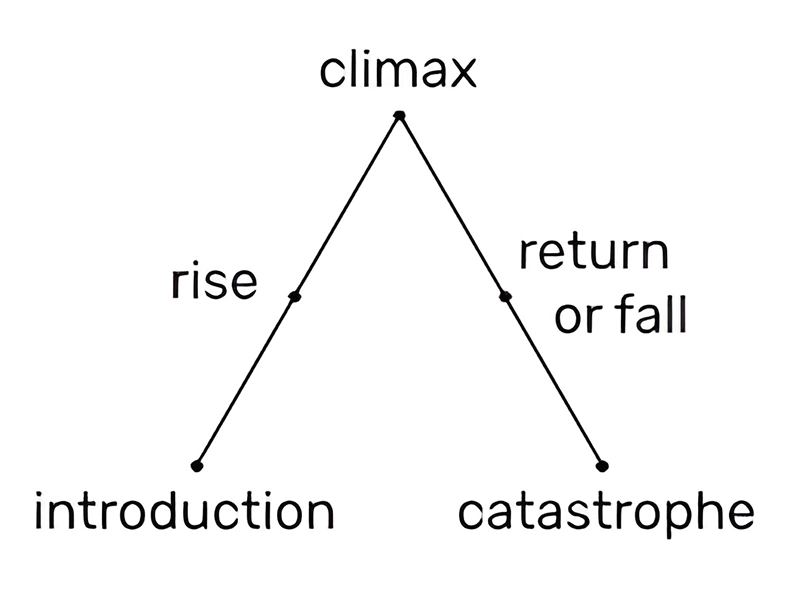

At its simplest, Freytag’s model slices a story into five beats: Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and Catastrophe (or resolution, depending on your genre).

1. Exposition (The Setup)

Here’s where the groundwork gets laid. We meet the characters, understand where and when the story takes place, and begin to sense the tone. It’s not just background noise—it’s the scaffolding on which everything else depends.

Good exposition feels invisible. It might show up through dialogue, a character’s internal monologue, a flashback, or even a prop that holds meaning. The key? Don’t overstay your welcome here. Too much setup, and readers might wander off before the story begins.

2. Rising Action (Where Things Heat Up)

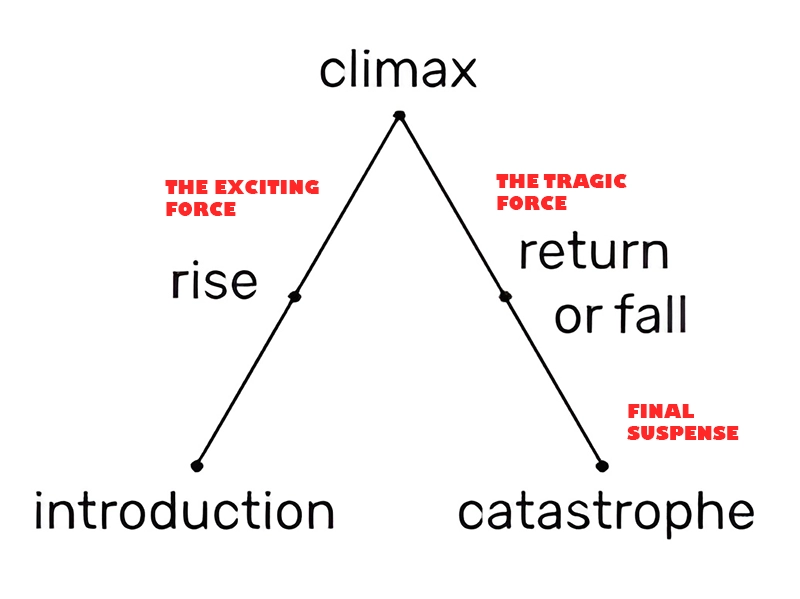

This stage kicks off with what Freytag called the “exciting force”—essentially the first real jolt to the story’s system. Maybe someone dies. Maybe someone lies. Maybe something simply goes terribly wrong. Whatever it is, it matters, and it changes things.

As the tension escalates, conflicts layer. These moments aren’t just filler—they’re the bricks that build toward the eventual peak. It’s a good idea to stretch this phase a bit; if everything climaxes too quickly, there’s nowhere to go.

3. Climax (The High Point or Turning Point)

Now we’re at the summit. Emotions peak. Stakes feel unmanageable. In tragedies, this is typically the moment when the protagonist’s fortune takes a nosedive—often thanks to a flaw that’s been there all along. In comedies or lighter stories, it’s more about the shift from struggle to breakthrough.

The climax is less about spectacle and more about consequence. It answers the question: What kind of story is this, really?

4. Falling Action (Descent and Consequence)

Once the climax lands, the story enters a kind of emotional freefall. Freytag labeled this the “return” or “fall.” It’s here that the protagonist must reckon with what’s happened—and the forces (sometimes external, often internal) that push them toward the end.

Importantly, Freytag urged simplicity here: fewer scenes, tighter focus. The noise of the rising action should give way to clarity—or chaos.

5. Catastrophe (Or Resolution, If You Prefer)

Despite the ominous name, not every catastrophe involves bloodshed or heartbreak. In comedies, this stage may just be the logical outcome that wraps things up neatly. In tragedies, however, the fall completes itself—often brutally. Freytag was adamant about this: no miraculous saves. A good ending feels earned.

That said, he did leave room for a “final suspense”—a sliver of hope right before the curtain drops.

Beyond the Basic Five: The Extra Crises

While the five stages are foundational, Freytag also noted three key crisis points that give stories more dimension:

- The Exciting Force – ignites the action.

- The Tragic Force – accelerates the fall.

- Final Suspense – teases a reversal just before the ending.

Think of these as narrative “pressure points” that, when used well, add complexity and emotional weight.

Genre Applications: Pyramid in Practice

- Tragedy: Think Greek theater, Shakespeare, or any tale where pride goes before a fall.

- Comedy: The pyramid flips; the descent leads to joy, reconciliation, or absurdity.

- Modern Stories: Films like The Lion King or series like Breaking Bad echo Freytag’s framework, even if unintentionally.

Using the Pyramid in Your Writing

A few practical moves for applying Freytag’s structure:

- Map out the five (or eight) parts before drafting.

- Pinpoint your turning points: What truly shifts the story?

- Let tension breathe; don’t resolve too quickly.

- Use final suspense to keep readers guessing.

Pitfalls to Avoid

- Info-dump Introductions: Get to the action. Readers need stakes, not an encyclopedia.

- Climactic Letdowns: If the climax doesn’t punch, the whole pyramid crumbles.

- Abrupt Endings: A rushed resolution feels cheap—even in short stories.

Why It’s Still Useful

Freytag’s model does more than organize plot—it shapes emotional rhythm. It keeps readers engaged, ensures movement, and offers structure without strangling creativity.

- Better Engagement: Keeps readers emotionally invested.

- Clearer Arcs: Helps avoid meandering or flat narratives.

- Stronger Coherence: Connects beginning, middle, and end more organically.

Quick FAQs

Q: Is this only for tragedies?

Not at all. Freytag designed it for drama, but it’s surprisingly flexible—across genres and mediums.

Q: What’s the difference between climax and catastrophe?

The climax shifts the story’s direction. The catastrophe resolves it.

Q: Does it work for short stories?

Absolutely. You’ll just need to compress the stages.

Q: How does it differ from the three-act structure?

Freytag’s version is more granular, offering five (or eight) beats instead of three sweeping acts.

Q: Do today’s movies still follow it?

Yes—many do, consciously or not. Titanic, Star Wars, Black Panther—they all echo the rise-climax-fall shape.

Q: Must every story end in catastrophe?

Nope. For some, catastrophe just means resolution—with or without ruin.

Why Freytag Still Matters

Freytag’s Pyramid isn’t just a relic of classical drama—it’s a flexible, time-tested tool for building stories that stick. Whether you’re sketching a novel, scripting a short film, or crafting a brand narrative, this structure offers a reliable blueprint.

Master the stages. Embrace the crises. And remember: great stories rise, turn, and fall—not always how we expect, but always with purpose.

Date Modified: 10-29-2025