Unmasking the Secrets of Noir and Hardboiled Fiction

By Lothar Tuppan

It’s Noirvember! Time to enjoy all things Film Noir, Roman Noir, Chocolat Noir, and Pinot Noir. Silly as that last sentence was, it does make plain that the French word “noir” just translates into English as “black.” So what exactly is “noir” in relation to cinematic (“Film Noir”) and literary (“Roman Noir”) fiction? What is its relationship with the, often associated, term “Hardboiled,” and what is its connections and relationship to Existentialism, Nihilism, and Philosophical Pessimism? This short essay is just a very brief introduction to a, surprisingly, complex topic. Whole books have been written on the subject (see bibliography below for some examples) and I encourage those who find the topic as fascinating as I do to pick them up.

Part of the problem with deciding what defines “Noir” is that it isn’t a simple taxonomical genre like “Mystery” or “Romance” or “Horror” (1). Despite the French title that came out of film criticism (first used by French critic Nino Frank) (2), what people call “Noir” is far more dynamic and organic than most genres. I’ll list some of the complexities as an illustration of how tricky of a subject it can be before exploring each in a bit more detail.

Perhaps the first thing to make clear is that the term was applied in 1946, after the fact, to films that had certain “black” qualities—as in emotional, physical, and moral darkness. Those examples of Film Noir (“black film”) were often adaptations of earlier Roman Noir (“black novel”). Later Roman Noir stories and novels were also influenced by Film Noir in a sort of feedback loop.

Film Noir owes much of its aesthetics and philosophy from the German Expressionism of the first three decades of the 20th century.

Roman Noir not only owes a certain debt of influence from the earlier Gothic literary movement but the term, Roman Noir itself, was originally used to describe the Gothic literature of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Both Film and Roman Noir were, in some ways, fictional explorations of philosophical conceptions that were working their way through the post-Darwinian, post-Nietzschean, post-Shopenhauerean, post-Freudean collective psyche (3).

Also, some of the examples of Film and Roman Noir also have a strong addition of the “Hardboiled” (either language, characterizations, or morality) which has similar connections to the aforementioned Existentialism (especially as a stylistic use of language) as well as being an updating of a specifically American genre (the “Western”) and archetype (the “Gunslinger/Cowboy”).

The term “hardboiled” or “hard-boiled” was first used in recipes from the 1730s referencing “hard-boiled eggs.” Mark Twain was the first to use it with regard to language describing nonflexible rules of grammar in 1886. In the first years of the 20th century it was used to describe stiff clothing and hats and by the end of WWI it described a very morally inflexible person. Soon after it was used to describe cynical people who didn’t show much emotion and may not believe in much except their own code of honor (4).

The qualities of cynicism, self-reliance (whether justified or delusional), and acknowledgement of institutional corruption are where “Noir” and “Hardboiled” meet. But they aren’t synonymous.

Perhaps discussing the philosophic foundations of their similarities, and then moving into their differences, will be a good way to approach this.

In the beginning of the 20th century a lot of people were trying to wrestle with the argument that there was no God. That we were biological entities that had evolved into what we are instead of being divinely created in the image of a supreme being that had a plan. Suddenly, we had no collective “meaning.” We weren’t here because of some numinous, albeit ineffable, intent but instead are just a happy accident.

Many philosophical schools came out of this psychic turmoil and while philosophers can argue about which threads were more or less prevalent, for the purposes of this short essay, there were some philosophical concepts that are core to Hardboiled fiction as well as both Film and Roman Noir.

- We have no inherent meaning as individuals or as a species.

- Any moral judgment on us is determined by our actions.

- Without a divine meaning or plan, we can determine our own meaning (this is especially prevalent in Hardboiled stories with Hardboiled characters).

- We don’t have as much free will as we believe. We might be organic machines, like in the new assembly lines, that just fulfill a biological function. Even without religious entities we still might be as “destined” as we ever conceived of. Just dancing puppets who can’t see their strings.

- Our past is inescapable, especially a past filled with poor or anti-social choices and actions (this is especially prevalent in pure Noir).

- The world and humanity are corrupt, dark, and prone to bad actions (Noir) and any deviation from that can really only happen at the individual level (Hardboiled) or maybe that’s just another delusion leading the individual to ruin (Noir).

This bleak outlook, then mixed with the new philosophies of Existentialism and Absurdism in France when the French saw what had been going on in American film and literature and applied the term “Noir” retrospectively (5).

Now, that nihilistic view of life, while being omnipresent in Noir, was mitigated to a certain degree in the Hardboiled.

Here, I’ll make a distinction between Hardboiled as 1) a linguistic style and 2) as a type of world view and character definition. The two are strongly tied together but, as James M. Cain proved (6), one can have strong, Hardboiled language without what we recognize as a Hardboiled character.

Hardboiled language was influenced by a few key things that emerged from increasing urbanization and industrialization: 1) an increasing feeling of dehumanization within cities and on assembly lines; 2) the Great Depression; and 3) an emphasis on efficiency and technology.

The last, especially, helped directly influence a key feature of Hardboiled language, namely the shift from a primary use of synecdoche to metonymy. The two are very similar but, with regard to Noir and the Hardboiled, synecdoche can be used organically and symbolically to present the person and their inner life. Metonymy, “stresses the systemic, the mechanistic, the extrinsic…” (7). For a simple example, “He’s all heart” (representing a kind-hearted person) is a use of synecdoche while “Who’s the suit?” (representing a business person) is metonymy.

This can make for very powerful and evocative language that is very different from older, more traditional forms of prose.

Also, a new American minimalistic voice was appearing and the compact, direct sentences, combined with a use of metonymy and new allusions and metaphors, helped comprise what we think of as “Hardboiled” language.

William Marling, in The American Roman Noir: Hammett, Cain, and Chandler, explicates a great example of this in James M. Cain’s use of the word “shape” as a descriptor of the beauty of a female body.

Here are the examples of Cain’s use, followed by Marling’s point.

“Except for the shape, she really wasn’t any raving beauty…”—James M. Cain The Postman Always Rings Twice.

“Under those blue pajamas was a shape to set a man nuts…” and “I wasn’t the only one to know about that shape…”—James M. Cain Double Indemnity

“Before, she had been a pair of eyes, and a shape, something to get excited about. Now she seemed something to lean on, and draw something from, that nothing else could give me.”—James M. Cain Serenade

“The word shape, for example, has no referent as Cain uses it. It is an empty vessel that we must fill with meaning . . . Shape could be read a number of ways, as ‘buxom’ or as ‘slender.’ Mae West and Mary Astor were both available for substitution . . . The point is that shape is an open metonymic slot in a system of desire that we fill with our definitions in order to gain meaning from the narrative.” (8).

That is a powerful stylistic technique to create a tone of the world and the people in it. The prose style draws the reader more intimately into the story by their increased conscious and unconscious participation in the narrative.

But what about Hardboiled characters? Many people have pointed out the direct connection between the preeminent American mythic archetype, the cowboy/gunslinger and the later private investigator. The solitary “emotionally untouchable man” (9) who has a strong moral code (albeit one that audiences might not always agree with) who encounters societal chaos (“black hat” bad guys in Westerns and “criminals” in Detective fiction) and puts things to right again with his mind, his guns, and his fists. Outsider heroes in the liminal spaces in society. Never quite fitting in as they have to traverse the worlds of respectable society as well as the violent world that would prey upon that society.

That violent, predatory world is also where the Hardboiled and Noir meet perfectly and that perfect pairing is one of the reasons people often see the both as synonymous.

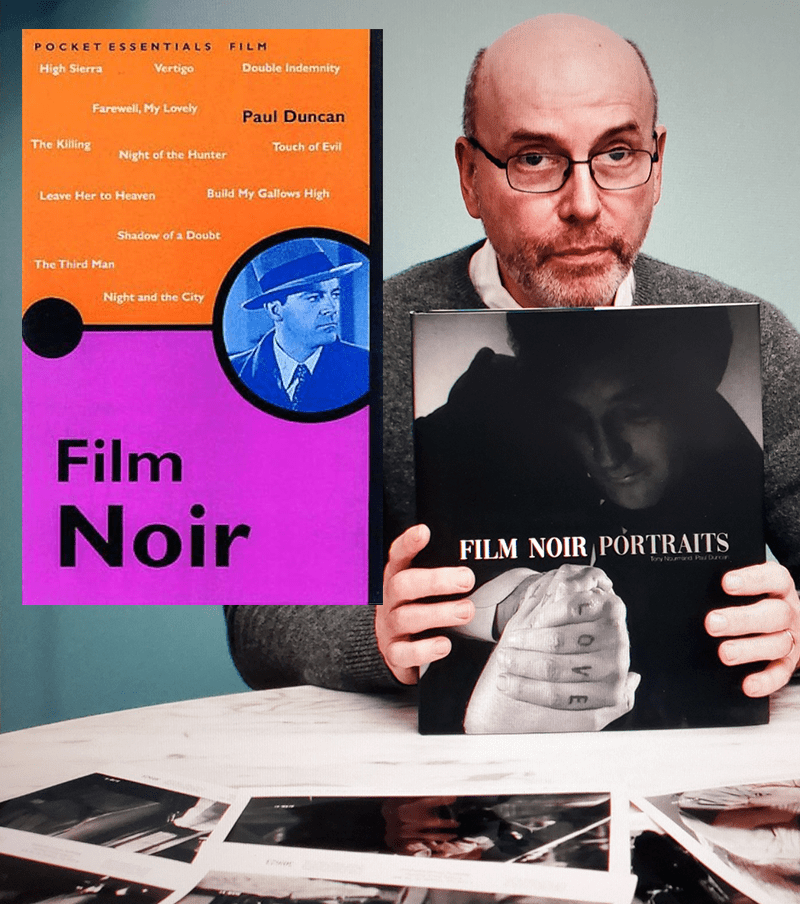

Paul Duncan describes the world of Noir (while he is specifically referring to Roman Noir it also applies to Film Noir) so beautifully that it is worth quoting at length.

“Noir is all those things we fear in the back of our minds, the parts of ourselves we want to block out because they make us feel uneasy. Noir doesn’t always have pat solutions and attractive people, doesn’t spoon-feed safe fantasies into drooling mouths. Noir drags you screaming and kicking through all sorts of hell before reaching some sort of unsatisfying ending. It’s not something that many people can take.

“Noir requires emotional commitment from the reader. The reader must be prepared to expose themselves to thoughts and feelings they’d rather not think or feel, and that’s a hard thing to ask. At best, you can learn something about people and yourself. It all depends upon how much of the Noir you are willing to recognize in yourself.

“Noir is often associated with the crime, detective and thriller genres because they give ample opportunity for you to gaze into the minds of bad, dark people on the edge of society. There is little chance of these characters invading your secure privacy. This is the fallacy, These people are actually you. They live and express your secret desires, weaknesses, and motives. It is safer for the character to live for you than for you to admit your dark side to yourself. The crime, mystery, thriller and detective clichés are a code to protect you, a wall you build to stop yourself from being hurt.” (10)

All of the aesthetic elements of Noir (the Chiaroscuro lighting, constant smoking, urban decay, clothing, etc.) and the stereotypical characters (the Femme Fatale as a most notorious and controversial example)—which are commonly the first things people think of when they hear the words “Hardboiled” or “Noir”—all reinforce the “Noir” and “Hardboiled” philosophies and world views semiotically. Those elements draw us in to dark, romantic, nightmare worlds that seem as fully formed as they seem stylized and expressionistic.

To complete our brief foray around the outskirts of these dark neighborhoods of human corruption and betrayal, I can imagine the casual tourist thinking that not all Noir is that completely dark and depressing. And they would be right. As I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, Noir isn’t a simple category of easy definitions and, as a more organic thing, people play with the levels of darkness in varying ways. To this end, some scholars make a harsh distinction between true “Noir” and the “Gris” (grey) stories where a more traditional happy ending might be present (like in Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat or in most old time radio drama adaptations of Noir and Hardboiled material).

Practically, the purest, darkest, Noir isn’t palatable for a mass audience. Sometimes people just need a little escapism and a happier ending to make the bitter realities go down easier. And publishers and film studios like a wide appeal that sells books and movie tickets.

This essay only scratches the surface of the topic. Others might bring up (and others have, see my bibliography below) the way that the European Naturalists, the Surrealists, Proletarian writers reacting to a post-industrialized world, and increasing urbanization contribute to Noir. Or they might focus on the activist (albeit cynical) nature of many Noir writers, or any number of other facets of this darkly beautiful and complex gem.

What I’m hoping you, gentle reader, take away from this modest primer is that Noir is a dynamic and complex topic. It’s not a genre with a simple definition. It’s not just a cinematic style involving Chiaroscuro lighting or stories that have stereotyped detectives or sexist Femme Fatales.

It’s more than a type of story regarding temptations and criminality with a particular aesthetic style; it is at its core an ontology with a strong philosophy behind it (with strong strains of Existentialism, Absurdism, and a bit of Nihilism). It’s a style and a type of story based upon a specific world view with certain philosophical assumptions.

And Noir has far outgrown its origins in film or prose fiction. It now is a fascinating body of film, literature, stage plays, comics, video games, and even music (“Jazz Noir” is a subgenre of Jazz music, for example).

The outer aspects of Noir (the style, the clichés, the conventions) might go in and out of fashion and trendiness, but as long as we still feel those dark impulses we (mostly) repress; as long as we avoid that dark alleyway or that dive bar, fearing what they might hold; as long as humans still lie, cheat, and betray each other, Noir will not be obsolete.

The darkness isn’t going anywhere and we will still need ways to deal with those harsh realities in our art as we keep stumbling “down these mean streets” (11) trying to make sense of, what might just be, a completely senseless world.

Notes

- “The film noir is not a genre, as the western and gangster film, and takes us into the realm of classification by motif and tone.” Durgnat, “Paint It Black: The Family Tree of the Film Noir,” in Silver and Ursini, Film Noir Reader, 38.

- Frank, Nino “Un nouveau genre ‘policier’: L’aventure criminelle,” L’ecran français 61 [1946]: 8–9, 14).

- See the various essays in The Philosophy of Film Noir, Conrad (editor) to explore the philosophical foundations and implications of Noir.

- Duncan, Noir Fiction: Dark Highways, p.8.

- For more comprehensive histories of these philosophical foundations see, Duncan, Marling, and Conrad.

- Three of Cain’s books (and the movie adaptations of them), The Postman Always Rings Twice, Double Indemnity, and Mildred Pierce are classic, foundational Noir novels which helped define what we consider to be Hardboiled language.

- Marling, American Roman Noir: Hammett, Cain, and Chandler p.XI. Also, Marling’s entire chapter, “Metonymic Sources” goes into far more detail as to the relationship between metonymy and Hardboiled language.

- Marling, pp.185-186.

- Duncan, p.9.

- Duncan, p.7.

- Chandler, Raymond, “The Simple Art of Murder” p.19.

Bibliography

Chandler, Raymond, “The Simple Art of Murder”

Clute, Shannon Scott and Edwards, Richard L., The Maltese Touch of Evil: Film Noir and Potential Criticism.

—Out of the Past: Investigating Film Noir podcast.

Conrad, Mark T. (editor), The Philosophy of Film Noir, 2005

Duncan, Paul, Noir Fiction: Dark Highways, 2000

Durgnat, Raymond, “Paint It Black: The Family Tree of the Film Noir,” in Silver and Ursini, Film Noir Reader, 1970.

Marling, William, American Roman Noir: Hammett, Cain, and Chandler, 1995

Schrader, Paul, Notes on Film Noir, 1972